E. Ethelbert Miller asks several questions: "Did you have long conversations with anyone prior to becoming a Buddhist? When should a person take his/her vows? How important is it to belong to a community? In your life have you ever experienced a moment of 'increased' awareness or enlightenment? What is the major distraction that often finds people 'straying' from the path?"

I will need two posts to address all these questions.

In this post, let me start by saying that I've been in conversations with Buddhists all over America since 1967, first with my teachers in the Asian martial arts, then with my professors, white, Chinese and Japanese, who taught the undergraduate and graduate courses I took on eastern philosophy (Hinduism and Taoism), and with others in the American Buddhist community such as Robert Thurman, a spokesman for the Dalai Lama, who I have lectured for twice at Columbia University and the Tibet House in NYC; mendicant monk Claude AnShin Thomas, with whom I took the ceremony for embracing the Precepts (I will discuss these in the next post); the publishers and editors for publications I write for like Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Shambhala Sun, and Buddhadharma; and many others during the course of my sixty years of living.

Probably one of the most moving, transformative encounters I had was in December, 1997 with a young abbot in the town of Phrae, who was building a meditation center in northern Thailand. I was there on a Microsoft-sponsored research trip to write an article on "The Asian Sense of Beauty" for their now-defunct on-line travel magazine Mungo Park. (My editor asked me to see if the rumor was true that Thai women are the most beautiful in the world; a comparable rumor among world-travelers is that Turks are supposed to be the most handsome men.) Let me talk first about my experience of that country---a poor, developing nation in need of jobs and education for its people, a place that is not free of political corruption and has feudal conditions yet is spiritually rich like India---before I discuss the abbot.

I knew as soon as my plane landed in Thailand, a country the size of Texas, that I was spiritually "home." It was like a trip to the Holy Land, one I didn't know I was making. But as I stepped off the plane, I felt a peace and calm descend upon me. I felt that so powerfully that during my first three days there I only slept two hours a day, because everything I saw manifested all the things I'd been studying about Theravada Buddhism since the 1960s. At Bangkok airport, I asked a young Thai taxi driver pushing a cart of luggage for directions, and he said to me, "You American? Welcome, soul brother," and he slapped my palm.

Thais date their history from the Buddha's birth---B.E., the "Buddha Era." In America we have posters of rock stars everywhere; in Chiang Mai ("New City") all the posters I saw were of revered Buddhist monks. There, we find as many statues of revered monks as we do the Buddha. At Doi Sutherp mountain temple, a Thai artist as he was working looked at me and my Scottish guide (I also had a young Thai guide named Uthai who spent 11 years in a monastery and was a monk for 9 days), and said, "You black, he white---you friends," and he seemed enormously pleased by that.

For two weeks I traveled to elephant training camps (100 years ago, there were 500 majestic elephants---which date back to end of the dinosaur age---for every person in Thailand, but in 1997 there were about 1300; there were once many species of elephants, now there are two, Indian and African) and to out-of-the-way locations most visitors never see (an illegal, wild animal market, for example, where I could not take pictures; I will not describe the things for sale there); to a Hmong New Year's house blessings conducted by a shaman, and the home of a Hmong opium-eater, who demonstrated for me how he took his drug. I interviewed the Thai people about their sense of beauty, performed many rituals and made many donations. In the journal I kept, I wrote, "Seeing Thailand, I realize what I've missed in America for 49 years, and why I was so powerfully drawn to Buddhism in my teens. This is a 'way of life' where the spirit and a worldly existence have not been separated---they are riabroi."

That Thai term has no English equivalent. Riabroi means "Everything together at once, complete, sensible, beautiful, perfect and natural." When the plane I took from an area near the Laos border (I spent a few days not only with Hmong hill tribesmen but also the Mabri "Yellow Leaf" forest dwellers who work for them) returned to Chiang Mai, the flight attendant said, "We have landed and everything is riabroi." A woman I interviewed said rather than having a handsome man, she'd much prefer being with one who was riabroi.

In my journal I also wrote: "It is as if the momentary 'home' I experience inwardly during meditation is all around me, externalized, outside and public everywhere I turn or gaze: the inner is outer, the Buddhist spirit manifested in the material world---in custom, ritual, objects for sale, paintings in my Empress Hotel room, in women (gasp!), in the greetings of hotel workers....I haven't met anyone here who is desperately trying to be funny or clever...There is something amazing about being in a culture, a country, where people aren't constantly criticizing and putting each other down, as we do in America. "Face' is lost if you disrespect another..'Respect' seems to permeate this culture---for the royal family, the spirits of the dead (animism) as seen in their spirit-houses, for foreigners, visitors, for monks. So far I have seen nothing disrespected. A young singer/showgirl I interviewed in a garden restaurant was asked by my Scottish guide if she'd ever seen a black person before. She said, yes, and she felt the ones she'd met had 'a good heart.'

"This culture is old, steeped in the compassionate spirit of the Dharma (and commingled with the animism that preceded Buddhism). Thais are always smiling, making themselves smile as a way to minimize conflict...It is as if the best of religion's principles (Buddhism) texture this society from top to bottom. The traditional crafts are here---from weaving to elephant training---and the modern is here, from computers to Latin music in the garden restaurant. But Thais value most a 'character' based on the model provided by the Buddhist monks....Perhaps, just perhaps, this journey was placed before me now, on the eve of my fiftieth birthday, for a reason; that is, so that I might find the energy and the resolve for the last stretch of living a life fully committed to the spirit. Question: in early 1998, should I join a Buddhist temple in Seattle? I know beyond all doubt after this trip, that Buddhism has been, and will be central to my life. Isn't it time, at age 50, to go yet another step along the Way? If that decision is made, the next ten years can be truly something thrilling to look forward to. Years of practice and meaning, greater perfection of the Dharma, and preparation for the final acts of this incarnation."

(A few years later, I was enrolled as one of the first members of Daigo-ji Temple in Japan by my friend, the late Zen priest Martin Hughes, one of the only two white abbots in Osaka, Japan in the early '90s; he once trained in the kung-fu studio my friends and I operated in Seattle, but died during a trip to the Philippines where he went to do work helping street kids---he ate something and died from food poisoning---and his temple closed.)

I could go on and on about Thailand, but now I should talk about the abbot.

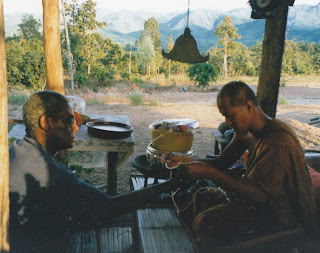

Our two-hour encounter was inspiring. I came prepared with twelve Dharma questions for him. When we were introduced his first remark was about how my hair was curly like that of the Buddha. (Women at the wild animal market also found my hair fascinating and asked me what I did to make it curly.) Normally, he spoke to visitors for only thirty minutes. But we hit it off immediately. He told me he would never be part of the religious hierarchy because it is drenched in politics. Instead of being involved with that, he was devoting himself to building a meditation center for the common people. We talked for two hours about a great many things: the nature of merit (karma), how Buddhism is about freedom even from Buddhist concepts, texts, and traditions. He showed me a 200-year-old palm-leaf manuscript, and one on paper that was 100-years old. These texts (he said) were just bridges that (like rituals) must one day be left behind. He emphasized the mind's development, the necessity of its freedom from illusion. His focus was on mindfulness at all times, i.e., knowing where one's mind is, on awareness during breathing exercises. And he valued meditation, which is something not true for everyone in Thailand. He studied me and predicted I would realize Buddha-nature.

For this abbot, truth was found in a free mind that is completely aware of the moment, of itself, and what it is doing, and of the body. He saw the many rituals he was called upon to perform as simply being "bridges" to Buddhism's deeper truths, merely "shadows" of the truth, but he dutifully met the laity where they lived, doing the rituals they asked for ---blessing a home, etc. He told me that some would understand the Dharma in 7 days, others would take 7 months, and still others wouldn't understand after 7 years, if at all. I performed one ritual with him; he gave me a meditation rosary, then he tied a string around my wrist and instructed me to wear it until it fell off, which I did---for several months and during the 6-week book tour I did the following year for Dreamer. He told me when his meditation center was completed, I could stay there anytime.

Lastly, the abbot expressed the view that Buddhism would be good for Americans. Why? Because America is a developed country, he said, one where people were free, and had the leisure time to study Buddhism and practice meditation. That was not true for the average person in Thailand. The American political system is admired world-wise, and especially in this country, where next door in Burma (Thai and Burmese cultures overlap) Aung San Suu Kyi was kept in house arrest for so long.

I was filled to overflowing on my flight back to America. (I returned with a begging bowl and monk's robe, which is still in its plastic wrapping, items I purchased at a place where monks shop, and I'd never dare put on that robe, but these items rest near one of my places for meditation and are reminders for me of the life I would probably lead if I was not a householder and writer/artist with worldly duties.) However, before my plane landed at Sea-Tac airport, the on-line magazine Mungo Park was canceled and its editors reassigned. In other words, Microsoft paid me for a glorious, life-altering, $5,000. research trip and an article that I no longer was expected to write (but I still have a notebook full of material I may some day use).

So to answer Ethelbert's question: yes, community---the Sangha---and communing with others is important, one of the Three Jewels of Buddhism in which we take refuge (along with the Buddha and the Dharma). But as the abbot of Phrae told me, one progresses alone, what one experiences can not be shared by another, and nothing can interfere with one's progress to liberation.